PRINCIPLES OF UNCERTAINTY | LOTTA ANTONSSON

03 May – 28 June 2025

Dorothée Nilsson Gallery is pleased to present Lotta Antonsson’s third exhibition at the gallery. In Principles of Uncertainty, Antonsson is loosely inspired by the scientific concept that there are inherent limits to what can be known and measured. The very act of observing changes what is observed – leading to reflections on how our perceptions shape our reality. Her current work reflects this tension. Principles of Uncertainty is not about answers. It’s an invitation to look differently, and perhaps to feel differently.

Antonsson belongs to a generation of artists shaped by the post-structuralist approach to identity and its formation: the self is not an essence but a signifier – a social, cultural and historical construct in flux. Subjectivities are shaped, negotiated and reinvented through the ways in which they are seen, interpreted and discussed. Nowhere is this more extreme than in the construction of female subjectivity. As John Berger once observed: “The social presence of a woman is different in kind from that of a man. A woman must continuously watch herself. She is almost always accompanied by her image of herself. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at” (Ways of Seeing, 1972). Unlike men, women are not merely represented: they have internalised the gaze as a condition of their own existence.

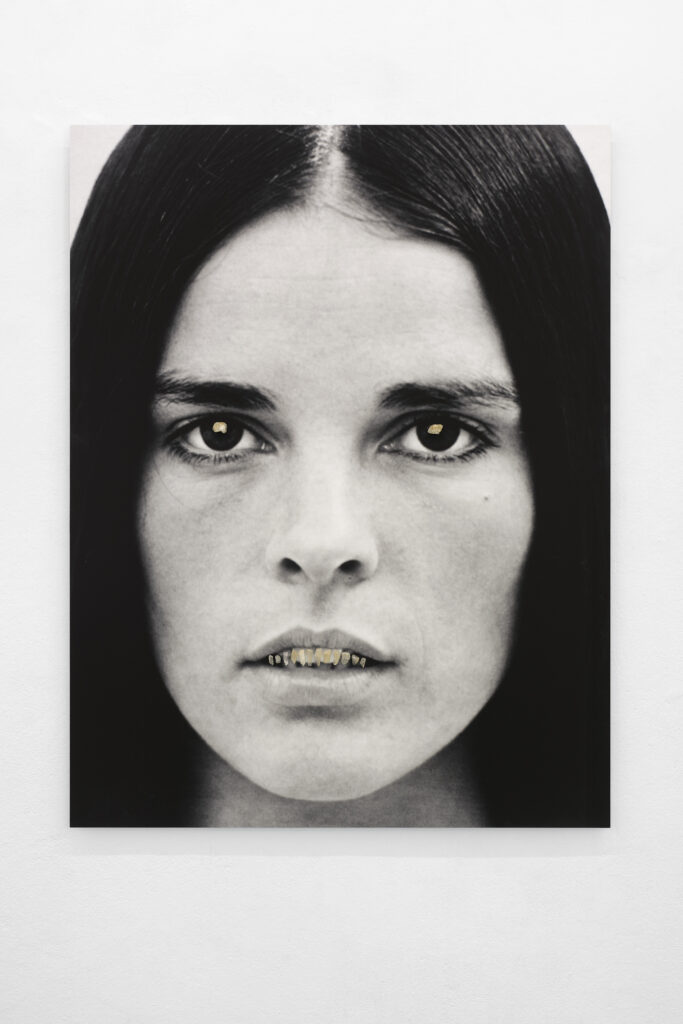

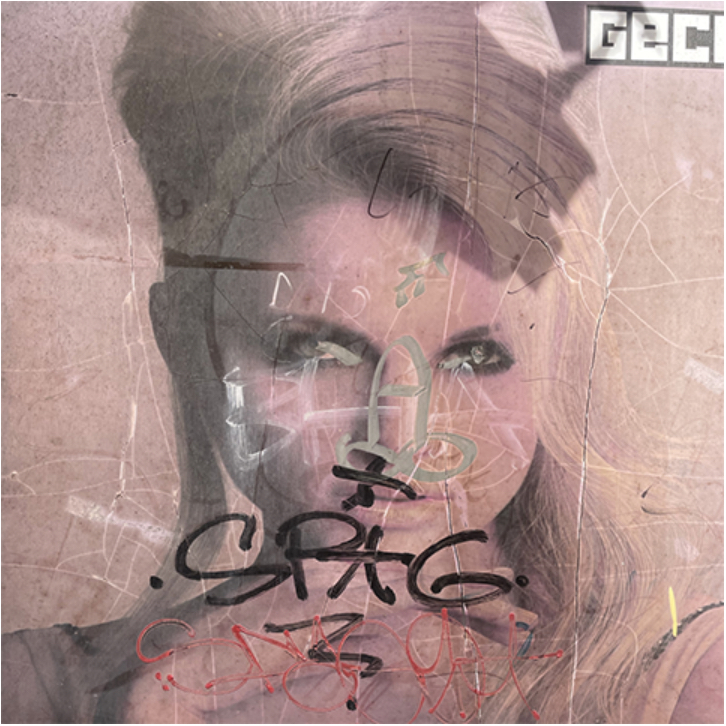

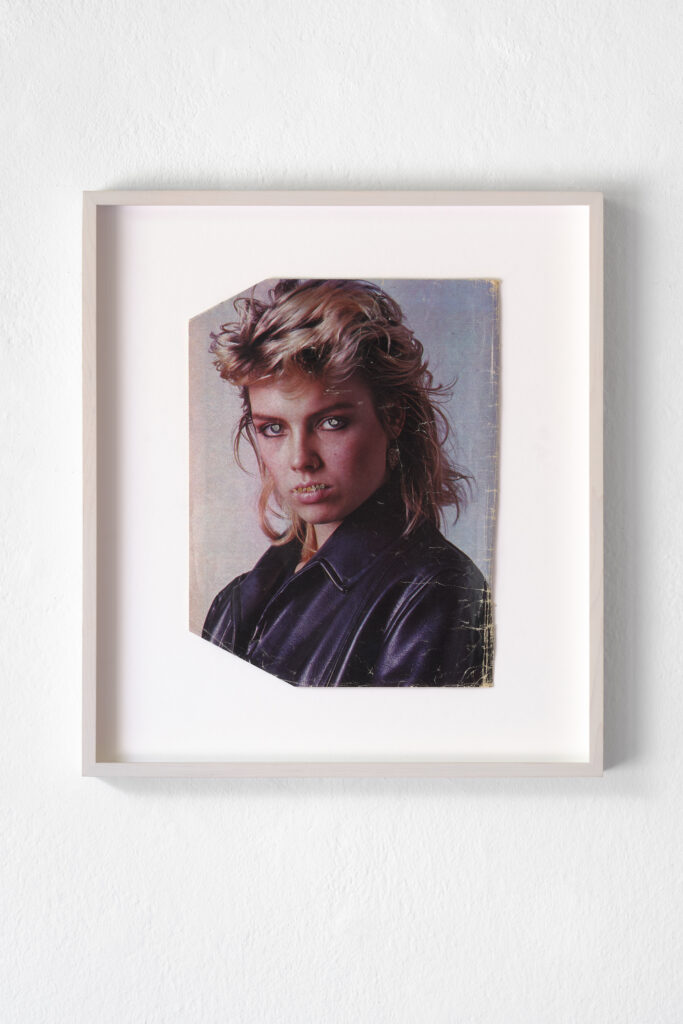

Antonsson’s work is a meditation on the metaphysical tension between presence and vision – both within the individual and the social body of women. Using analogue processes of photography, collage and assemblage, she dismantles and reconfigures the visual language that has historically framed femininity, revealing the gaze as both a mechanism of control and a tool of liberation. Drawing from a personal archive of vintage lifestyle and erotic magazines, she examines how women’s bodies have been represented, desired and consumed. Cutting, layering and recontextualising found images, she creates a fractured, ironic space where clichés are exposed and the authority of representation is momentarily suspended.

The artist approaches collage not only as a visual strategy, but as an act of disruption. She intervenes in the historical narratives they carry. Often the eyes of the women in her collages are covered, obscured or removed altogether. A seashell may obscure the gaze, a crystal may take the place of a mouth. These gestures are small refusals – gentle but insistent. If, as Berger wrote, „a woman must continually watch herself”, what does it mean when she closes her eyes? Can it be a kind of freedom – a way of stepping out of the endless performance of being seen? In addition to paper and print, Antonsson works with shells, amethysts, coral and crystals. She sees them as material metaphors – carriers of meaning, of the past, of memory and sensation. They are armour and ornament, magic and silence. Their presence disrupts the flatness of the picture and reminds us of texture, touch, weight. Something physical. Something alive. We live in a culture of endless image production, where the photograph is so often stripped of time, place or meaning. The artist is interested in what happens when we pause this cycle – when we take an image and slow it down, make it strange, give it space to breathe. Her work lives in this space: between beauty and discomfort, history and invention, surface and depth.

Lotta Antonsson studied fine arts and photography in Stockholm at the University of Arts, Crafts and Design and at the Royal Art Academy in Copenhagen. Antonsson was a professor of Photography (2007-2016) at the Valand Academy of Art and Design in Gothenburg. Her works have been in numerous international exhibitions, including Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Magasin III, Stockholm, Capture Photofestival / Trapp projects, Vancouver, Villa San Michele, Capri, the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art in Riga, Photo Biennale in Brighton, UK, and the Daegu Photo Biennale in South Korea. Her work is in several international collections, among them Moderna Museet, Stockholm, SE, The Gothenburg Museum of Art, Gothenburg, SE, Hasselblad Foundation, Gothenburg, SE, Magasin III, Stockholm, SE, Hallands Konstmuseum, Halmstad, SE, Soho House, Stockholm, SE, Swedish Art Council, Stockholm, SE, Sammlung Hackelsberger, Berlin, DE

Die Dorothée Nilsson Gallery freut sich, die dritte Ausstellung von Lotta Antonsson präsentieren zu dürfen. In „Principles of Uncertainty” lässt sich Antonsson von dem wissenschaftlichen Konzept inspirieren, dass es inhärente Grenzen für das gibt, was man wissen und messen kann. Schon der Akt des Beobachtens verändert das Beobachtete, was zu Überlegungen darüber führt, wie unsere Wahrnehmungen unsere Realität formen. Diese Spannung spiegelt sich in ihren aktuellen Arbeiten wider. In „Principles of Uncertainty” geht es nicht um Antworten. Es ist eine Einladung zum anders Sehen und vielleicht auch zum anders Fühlen.

Antonsson gehört zu einer Generation von Künstlern, die vom poststrukturalistischen Ansatz der Identitätsbildung geprägt ist. Das Selbst ist keine Essenz, sondern ein Signifikant – ein soziales, kulturelles und historisches Konstrukt in stetigem Wandel. Subjektivitäten werden durch die Art und Weise, in der sie wahrgenommen, interpretiert und diskutiert werden, geformt, verhandelt und neu erfunden. Nirgendwo ist dies ausgeprägter als bei der Konstruktion der weiblichen Subjektivität. Wie der Schriftsteller John Berger einmal feststellte: „Die soziale Präsenz einer Frau ist anders als die eines Mannes. Eine Frau muss sich ständig selbst beobachten. Sie wird fast immer von ihrem Bild von sich selbst begleitet. Männer schauen Frauen an. Frauen sehen sich selbst dabei zu, wie sie angeschaut werden“ (Ways of Seeing, 1972). Im Gegensatz zu den Männern werden die Frauen nicht nur dargestellt. Sie haben den Blick als Bedingung ihrer eigenen Existenz verinnerlicht.

In Antonssons Arbeiten ist die metaphysische Spannung zwischen Präsenz und Vision – sowohl innerhalb des individuellen als auch des sozialen Körpers der Frau – spürbar. Mithilfe analoger fotografischer Verfahren, Collagen und Assemblagen demontiert und rekonfiguriert Antonsson die visuelle Sprache, die die Weiblichkeit historisch geprägt hat, und enthüllt den Blick sowohl als Kontrollmechanismus als auch als Werkzeug der Befreiung. Ausgehend von ihrem persönlichen Archiv alter Lifestyle- und Erotikmagazine erforscht sie, wie Frauenkörper dargestellt, begehrt und konsumiert wurden. Indem sie gefundene Bilder ausschneidet, schichtet und neu kontextualisiert, schafft sie einen gebrochenen, ironischen Raum, in dem Klischees entlarvt werden und die Autorität der Darstellung für einen Moment außer Kraft gesetzt wird.

Die Künstlerin nutzt die Collage nicht nur als visuelle Darstellungsform, sondern auch als Akt der Störung. Sie greift in die historischen Narrativen und deren Bedeutung ein. Oft sind die Augen der Frauen in ihren Collagen abgedeckt, verdeckt oder ganz entfernt. Eine Muschel verdeckt den Blick, ein Kristall nimmt den Platz des Mundes ein. Kleine Verweigerungen – sanft, aber eindringlich. Wenn, wie Berger schrieb, „eine Frau sich ständig selbst beobachten muss”, was bedeutet es dann, wenn sie die Augen schließt? Ist es eine Art Freiheit – ein Heraustreten aus der endlosen Vorstellung, gesehen zu werden? Neben Papier und Druck arbeitet Antonsson auch mit Muscheln, Amethysten, Korallen und Kristallen. Sie betrachtet sie als materielle Metaphern, als Träger von Bedeutung, von Vergangenheit, von Erinnerung und Empfindung. Sie sind Rüstung und Ornament, Magie und Stille. Ihr Vorhandensein durchbricht die Flächigkeit des Bildes und erinnert uns an Textur, Berührung und Gewicht. An etwas Körperliches. An etwas Lebendiges. Wir leben in einer Kultur der endlosen Bildproduktion, in der Fotografien oft frei von Zeit, Ort oder Bedeutung sind. Die Künstlerin interessiert sich dafür, was passiert, wenn wir diesen Kreislauf durchbrechen, wenn wir ein Bild nehmen, es verlangsamen, ihm Raum zum Atmen geben, es verfremden. Ihre Arbeit bewegt sich in diesem Spannungsfeld zwischen Schönheit und Unbehagen, Geschichte und Erfindung, Oberfläche und Tiefe.

Lotta Antonsson studierte Bildende Kunst und Fotografie an der Universität für Kunst, Handwerk und Design in Stockholm sowie an der Königlichen Kunstakademie in Kopenhagen. Von 2007 bis 2016 war sie Professorin für Fotografie an der Valand Academy of Art and Design in Göteborg.

Ihre Werke waren in zahlreichen internationalen Ausstellungen zu sehen, u.a. im Moderna Museet und im Magasin III in Stockholm, beim Capture Photofestival/Trapp Projects in Vancouver, in der Villa San Michele auf Capri, im Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art in Riga, auf der Photo Biennale in Brighton (UK) und der Daegu Photo Biennale in Südkorea. Ihre Arbeiten befinden sich in mehreren internationalen Sammlungen, u.a. im Moderna Museet in Stockholm, im Göteborgs Konstmuseum in Göteborg, in der Hasselbladstiftelsen in Göteborg, im Magasin III in Stockholm, im Hallands Konstmuseum in Halmstad, im Soho House in Stockholm, im Swedish Art Council in Stockholm und in der Sammlung Hackelsberger in Berlin.